In the past few years in both the United States and Europe, populist movements have made their way into mainstream politics from their previous positions on the ideological fringe. The reason for this proliferation is repeatedly debated and has much to do with the global crisis of the political establishment, which has seemingly failed to stay in touch with their respective electorates. Furthermore, the explosion of various issues has led people to vote, in increasing frequency, for populists that threaten to break the political status quo.

Background

Formerly confined to Italy's Lombardy and Veneto regions, the Northern League has brought its right-wing populism into the mainstream, as it has become the most potent right-wing political force in Italy. In the recent election on March 4th, 2018, the Northern League carried 17.69% of the vote, surpassing former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party as the preeminent conservative force. This article’s analysis seeks to understand the characteristics of the League that make it a populist movement in addition to the themes it has evoked to deliver its message as well as its ability to transform itself from a regional to national political force.

Populism

The concept of populism is hard to define, and political scientists have trouble agreeing on a specific definition given its nebulous nature and its ability to manifest in different ways according to the context. The definition I have chosen to work off of is that of Cas Mudde. Mudde in “The Populist Zeitgeist” defines populism as "an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, 'the pure people' vs. 'the corrupt elite' and which argues that politics should be an expression of the general will of the people", (543). This widely-cited definition claims populists commonly articulate a specific juxtaposition between "the good people," also referred to as "the heartland," and "the corrupt elite". This conception of populism allows us to understand how these two homogenous and antagonistic groups serve as categories that can assume different meanings according to the context the movement operates in. The moral division between the “good people” and the “bad elites” is articulated in a specific way by right-wing populist groups, who emphasize a more exclusionary and nativist conception of "the people" or "the nation".

The Northern League

Founded in 1991 by a man named Umberto Bossi, the party's politics initially targeted a certain kind of 'Northern Italian people;’ consisting of Italians from the regions of Lombardy, Veneto, Tuscany, Piedmont as well as several other northern regions in what they call “Padania.” Bossi's inflammatory rhetoric emphasized the economic disparity between the North and South and demonized the central government in Rome for its corruption. Under his leadership, the party focused on campaigning for Northern Independence, propagating strong secessionist politics that in established the Northern League as a strictly regional party. Bossi's rhetorical application of populism referred to "the authentic people" as northern Italians, who feel particularly antagonized by the “corrupt elite” which they claim sit in central government and southern Italians, who don't share the same values and principles of productivity as the North. Since rebranding, the League has gained much support in the recent election as it shed the identity created during Bossi's premiership. Since Matteo Salvini’s accession to the leadership position in 2013, the League's populist rhetoric has distinctly shifted to include all Italians, while positioning anti-immigration and hostility toward the European Union as its central creeds. Through this, the League casts itself as an “underdog party” fighting against a system of bureaucrats and elites.

Early Propaganda

By closely observing the League's early campaign posters from 1990 to 2010, the themes that dominate the party’s politics are made clear. In each of these three examples, the virtuous people of the Northern Padania region are called upon to rebel against the central government in Rome. Here Rome is clearly labeled as the bad elite, by being repeatedly addressed as "Roma Ladrona" or "Rome the thief", pointing to the immorality and inefficiency of the government that supposedly wronged Bossi's constituency. The idea of "the people" that was being constructed by the party under Bossi's leadership was clearly limited to Northern Italians as demonstrated by these posters, the third of which pictures Bossi arguing for Northern independence and stating: "farther away from Rome, closer to you".

“Figure 1: Lega Nord Posters under Bossi”

Bossi's aggressive characterization of Rome's central government as being a "thief" evokes a number of meanings. In the early years of the Northern League, Bossi continuously reinforced the message that the politicians in Rome were corrupt and inefficient, while presenting his party as a people-oriented alternative. It is curious to note that Bossi made strong allegations during the crisis known as "Tangentopoli." This nationwide judicial investigation into political corruption during the 1990s, saw the disappearance of many political parties, while reinforcing the populists’ message that the central government was inept and dishonest. Within this context, the portrayal of Rome as a thief felt justified in the eyes of the people, given the raft of bribery, plundering of public coffers and more. The Tangentopoli scandal presented Bossi with an ideal scenario: ride the wave of disaffection with the political class and present himself as the ideal political leader.

Ascendance to the National Stage

The first time the Northern League established itself as a significant political force in Italy was during the general elections of April 1992, in which it secured the fourth highest share of votes, behind the Christian Democracy Party (DC), the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) (Sciortino, 326). Despite this success and its newfound national prominence, throughout the 1990s, the Northern League continued to advance its regionalist position, advocating for secession for the north and refusing alliances with any other Italian party. It becomes clear that under Bossi's leadership, the party would continue to articulate the antagonistic relationship between the Italian North and the rest of the country. This is despite a brief alliance with the dominant national parties, such as Berlusconi’s Forza Italia in 1994. As a result, it continued to exist as a regional phenomenon, who’s political support stemmed primarily from the North. Throughout his leadership, Bossi created divisions amongst Italians by portraying a stark difference between the “underdog” Northerners and the corrupt political elite of Rome – a viewpoint that has persisted decades after the party’s founding. For instance, these themes are echoed in a press release written by Bossi in 2007 stating "Rather than talking so much, those gentlemen in Rome should listen to the honest people who cannot take any more taxes. I know we cannot have a tax revolt using weapons, but the people are pissed off." It is important to note that Bossi's anti-establishment language was founded upon the accusation that the government was out of touch with 'the people' and indifferent to the needs of the north. With these allegations, Bossi effectively constructed a “Northern Italian” identity that connects with the productivity of Northern business but is weighed down by the corrupt bureaucracy and the un-productivity of the South.

Extremism at the Heart of the Party

Apart from spreading this rhetoric – advocating for secessionist politics – Bossi's early Northern League displays a darker, extreme right nature. From its early days, the party's exclusionary language spread hatred – first against the Southerners and later migrants. The three campaign posters included below reflect the strong nativist and xenophobic rhetoric that characterized Bossi's discourse as he established the Northern League as a protector of Italian northern people from being "invaded" by groups that are continuously “otherized.”

“Figure 2: Lega Nord Posters Illustrating its Narrative ”

The first poster (from left to right) pictures a group of supposedly Muslim people conducting prayer and contains inflammatory language that translates into "Enough is enough! Get out of here!” The second poster also targets Muslims by evoking Italian food traditions that resonate emotionally with the Italian electorate. By contrasting the traditional Italian polenta dish to Moroccan couscous grain with the words "Proud of our traditions", Bossi's language aims to demonstrate the impossibility of integrating these groups. Unlike the first two posters, the third speaks to the initial objective of the League: obtaining Northern Independence. This is done in part by identifying Southern Italians as "terroni", which is a derogatory term used to describe Southerners as having negative personal characteristics such as laziness and ignorance. This speaks to the Northern League’s origins as an explicitly-ethnic movement, primarily interested in preserving regional cultural differences and dialect, which were the most important elements in their early election campaigns. Given its roots, it becomes clear the party's political message sought to maintain a certain northern cultural uniformity. Therefore, the regional chauvinism expressed in these campaign posters explains the otherization of Southern Italians and their characterization as being ethnically different from Northerners, particularly in the early articulation of the League under Bossi's leadership. The alienation of the south is reflected in Bossi's inflammatory language present in anti-southern slogans, such as 'Africa Begins at Rome'. This language understandably stained the Northern League's reputation throughout the peninsula and has made it difficult for future leaders to recuperate credibility from the southern regions.

Shift in Rhetoric

As the party moved away from northern roots, it shifted the target of its rhetoric from southerners to immigrants, who's culture, they said, could not be integrated with that of Italy’s. As discussed by Giuliano Bobba and Duncan McDonnell in their analysis of this populist force, "although the League makes occasional references to homosexuals and southern Italians as 'others', the main 'other' for the party is immigrants, especially those from Islamic countries" (291). Therefore, once the party stopped seeing itself as a separatist force, it shifted its focus of the 'others’ threat' to immigrants. These sentiments are clearly portrayed in the campaign artifacts (shown above) that suggest that, in the eyes of Bossi and the Northern League, immigrants that disrupt Italy’s cultural homogeneity should leave.

With this shift in rhetoric, the Northern League aimed at constructing a common enemy for all Italians. Consequently, they began to depict immigrants as representing a security threat due to supposed links to terrorism as well as their alleged involvement in violent crime. Indeed, they sought to portray them as a threat to the core values of native Italians. Though, it is evident that their language targeted a certain type of migrant, who’s values are more asymmetrical to that of Italians, as opposed to European migrants. This shift was embraced fully by Matteo Salvini in his 2018 campaign as it became a central tenet of his political message as well as his promise to clamp down on illegal migration.

The Nature of Populism

Scholars have also pinpointed populism’s moralistic, as opposed to programmatic, nature as a defining element. In The Populist Zeitgeist, Cas Mudde describes populism as a thin-centered ideology that claims to speak in the name of 'the oppressed people', who populist leaders believe they are emancipating by making them aware of their oppression without intending to change their values or way of life (544). By establishing themselves as speakers for the 'common man,' populist leaders argue that established political parties have corroded the link between leaders and the electorate and claim their direct communication with the electorate and ability to 'say it like it is' makes them genuine representatives of 'the people'. Furthermore, in the aftermath of the 2018 Italian elections, the editorial board of the Guardian wrote on Mudde’s claims stating, "populists are able to promise the Earth while not dealing with the problems on it." Given the moralistic nature of populist parties, their campaigns seek to demonize their opponents, who’s values they see as the antithesis of the heartland and are unable to provide for the people they are supposed to serve.

The strong appeal to people's fears and emotions is frequently felt in today's discourse, which often leads to the misrepresentation of reality as well as the exaggeration of the threats facing society. This is abundantly clear in the case of Matteo Salvini's League as the party has chosen immigrants to be the main opponents due to their supposed inability to integrate with Italian culture. Despite having promised to halt African “invasion” into Italy, Salvini does not delve into how exactly he will do so – another demonstration of how the League is not a programmatic movement, but rather a movement that seeks to incite anger by aggravating emotions as opposed to making feasible promises. This view is reinforced by prominent writer, Ernesto Galli della Loggia, in a Corriere della Sera editorial, where he suggests the present political parties are making imaginative and unachievable promises to their electorate, and lack realistic application. To illustrate this point, he brings up the League's promise to remove all illegal immigrants, as he ironically asks himself, "how could we, for example, identify and round up the famous illegal immigrants scattered in the entire peninsula, to then deport them who knows where?" This further reinforces the notion that The League’s promises are of the moralistic variation.

Changing of the Guard

The leadership transition in 2013 from its founding father Umberto Bossi, to the present leader of the party, Matteo Salvini, has had numerous implications on the League and its reception amongst the Italian audience. In particular, Salvini’s revamp of the League's notion of the "heartland" has had profound effects on the party's rhetoric, especially as its new leader is determined to move away from Bossi's inflammatory language and reputation. Having chosen to become a national force, a major rhetorical shift was necessary in order to abandon its regional roots and brand themselves as protectors of Italians as a whole, rather than exclusively Northern Italians. In his 2018 electoral campaign, Salvini has made a fervent effort at courting the disaffected from all parts of the country, in a bid to challenge the rival populism of the Five Stars Movement. In an effort at re-branding the party, not to mention rectifying its stained reputation in the South as a result of Bossi's extremism, Salvini has attempted to advertise himself as a more accommodating and civilized figure than his predecessor. This attitude is manifested in one of his most common campaign posters, shown below in figure 3, in which he identifies his movement as being "The Revolution of Common Sense".

“Figure 3: La Lega Posters under the leadership of Salvini.”

This is despite the fact that it may not be "common sense" to consider immigrants as invaders, Salvini carefully picks these words to try and communicate that he is the best candidate to tackle the country's challenges. Also, in hopes of moving away from its past as a regional political insurgency, Salvini's rebranded movement simplified its name from the Northern League to simply the League, as shown in figures 3 & 4.

Nationalistic Turn

Another major shift, as a result of the Lega's change in leadership, is discussed in Insurgents against Brussels: Euroscepticism and the right-wing populist turn of the Lega Nord since 2013. In this, authors Marco Brunazzo and Mark Gilbert argue that the party has shifted from the demonization of central government in Rome to a strong antagonism towards the EU leading to a situation where "Brussels has substituted Rome in the movement's propaganda as the place where incompetent and corrupt elites exploit ordinary citizens" (625).

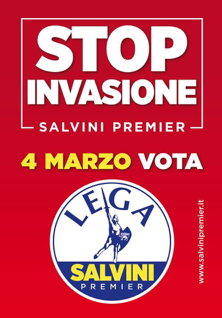

Having made immigration and Euroscepticism the main tenets of its campaign, under Salvini's leadership, the League has undertaken a strong nationalist turn. In figure 4, we see three samples of Lega posters put out by the League during Salvini's campaign for the recent 2018 election. These posters are significant artifacts that demonstrate the effective rebranding of the movement that took place under his leadership and, perhaps, is partially responsible for his recent electoral success.

“Figure 4: La Lega Posters Advocating for a “Stop of the Migrant Invasion.””

The first two posters (from left to right), reinforce the two themes that have been previously discussed regarding the change of the party's enemies from the 1990s under Bossi to the present under Salvini. The first poster emphasizes the League's commitment to "Stop the Invasion", which refers to Salvini's aggressive campaign against the mass migration of African immigrants to Italy. This slogan was repeatedly present in Salvini's rhetoric, to the extent that the League held rallies where members of Salvini's team were wearing "Stop the Invasion" t-shirts. Often, the slogan was strategically used to attack the ruling center-left Democratic Party (PD) of Matteo Renzi, who Salvini blamed for the handling of the migrant crisis. As a partial result of these attacks, we saw a weakened PD battered in the national election with their support waning throughout Italy. Throughout the campaign, Salvini made a strong effort to frame African migrants living in Italy via association to criminal acts, and therefore called for mass deportations. For instance, after a Nigerian man was arrested on suspicion of killing an Italian teenager on February 1, Salvini wrote on Facebook, "What was this worm still doing in Italy? The left has blood on its hands," (Appendix). By depicting migrants in this light, Salvini has made an effort of partnering with Europe's extreme-right on the issue of African migration, as proven by his open endorsement of both Marine Le Pen's National Front and Geert Wilders's Dutch Freedom Party.

The second poster from the left tackles another central tenet of Salvini's rebranded message, his deep Euroscepticism. The poster reads, "Enslaved by the European Union? No Thank You! Vote Lega," which serves to demonstrate the changing subject of the movement's "bad elite." The third poster carries another popular slogan from Salvini's campaign, "Italians First, Always," suggesting a more nationalistic tone akin to that of Donald Trump’s “America First” slogan and Nigel Farage’s Leave campaign. These posters are indicative of the effort to widen the party's audience and distance itself from its origin as a Northern phenomenon perpetrating an anti-Southern message. Given its new mission objectives, the party's populist discourse argues that the bureaucrats that must be displaced are no longer in Rome, but in Brussels. Through the choice of these “enemies,” which, according to Salvini's construction of them, can be perceived as threats to Italy, the League attempted to widen its base in the hopes of becoming a truly national force.

A Man of the People?

The electoral success of The League in the recent election is owed partly to the strategy adopted by its candidate to portray himself as an authentic common man capable of understanding the needs of "the Italian people". Salvini has made significant efforts to construct an image of himself that was relatable and genuine for his audiences, emphasizing his Italian identity and commitment to protect Italian culture. On top of being a strong television presence and organizing numerous rallies across the peninsula, Salvini's greatest tool to reach his electorate has been via social media. Having analyzed about 50 posts that Salvini shared through Facebook and Instagram between January 1st and March 4th, the candidate's success in delivering his message across these platforms is evident. As has been concluded by numerous scholars, populist discourse thrives through social media platforms in that it provides populist candidates with an ideal medium to instill a sense of direct communication with their electorate, circumventing the media, which has traditional ties to the mainstream parties. With 195,000 followers on Instagram and 2.2 million on Facebook, Salvini has been able to use these platforms to his advantage to advance his populist discourse by emphasizing slogans and hashtags, such as #StopUE and #StopInvasion. Through his posts, Salvini has attempted to construct a certain Italian identity, of which he made himself the spokesman, declaring himself as “the only candidate capable of liberating Italy because he loves the country and its traditions to his core" (Appendix). He attempts to deliver his commitment to his land by emphasizing what he believes to be core Italian values and traditions, which he attempts to convey by sharing numerous photographs of himself eating pasta, pizza, prosciutto and drinking Italian wine (Appendix).

“Figure 5: Instagram Posts from Salvini”

Two of the many posts that emphasize this theme of tradition and authenticity are shown in figure 5 above. By picturing Italian products and associating himself with Italian workers, such as artisans, farmers and small-business owners, Salvini emphasizes his populist credentials by underlining his capability to speak and represent the common man. The first post with Italian agricultural products intends to target all non-Italian products, particularly the European Union’s, with Salvini encouraging his followers to "choose Italian and buy Italian." In the same vein as his "Italians First, Always," the second post seeks to portray Salvini's commitment as the protector of the Italian people and the defender of their traditions. Through methods like this, the League sought to reassure Italians to fight for all of them as opposed to only the Northerners. Despite remaining highly controversial and extreme in its views, the League, under Salvini's leadership, distanced itself from the inflammatory language used by its founder, Umberto Bossi, in the hopes of presenting itself as a matured movement – one that is more able to govern the nation.

Overall, the League's electoral success in the recent 2018 election demonstrates an alarming rise in support for far-right political parties amongst the Italian electorate. By shifting the party's focus to immigration and Euroscepticism, Matteo Salvini has managed to disguise the party's political message by rebranding it to fit the fears and anxieties of Italian people as a whole. This is shown in figure 6 below, where Salvini’s right wing coalition managed to secure the greatest number of votes.

“Figure 6: Italian Election Results (the Economist)”

However, despite his effort to court the Italian south and erase the party's history as a separatist force, a geographical analysis of the vote demonstrates the League's support was concentrated in the North. It is important to note that in the Italian South, large swathes of people voted for the League's populist rival – the Five Star Movement, as shown in figure 7.

“Figure 7: Italian Election Results by Party (the Economist)”

Despite his effort to shift his characterization of "the people" and "the bad elites,” Salvini's supporters remain geographically concentrated in Italy's Northern regions. Nevertheless, the elections marked a major shift in the fortunes of the League as a national force that has given it greater agency as well as an official seat at the decision table.

Works Cited

Agenzia Vista. "No Bolkestein, Salvini in Piazza Con Gli Ambulanti: 'Direttiva Infame Contro i Lavoratori Italiani' ". YouTube, 28 Sept. 2016.

Agnew, John. “The Rhetoric of Regionalism: The Northern League in Italian Politics, 1983- 94.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 20, no. 2, 1995, pp. 156– 172. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/622429.

The Data Team. “The Italian Elections in Charts.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper Limited 2018, 5 Mar. 2018.

Editorial. "The Guardian view on Italian elections: A lesson for progressives." The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 5 Mar. 2018.

Galli della Loggia, Ernesto. "I Partiti e Le Promesse, Cambiare è Facile (a Parole)." Corriere della Sera. 27 Apr. 2018.

Giuliano Bobba & Duncan McDonnell (2016) Different Types of Right-Wing Populist Discourse in Government and Opposition: The Case of Italy, South European Society and Politics, 21:3, 281-299,DOI: 10.1080/13608746.2016.1211239

Henley, Jon and Antonio Voce. "Italian Elections 2018- Full Results." The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 5 Mar. 2018.

Marco Brunazzo & Mark Gilbert (2017) Insurgents against Brussels: Euroscepticism and the right-wing populist turn of the Lega Nord since 2013, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 22:5, 624-641, DOI: 10.1080/1354571X.2017.1389524

Mudde, Cas. "The Populist Zeitgeist." Government and Opposition, vol.39, no.4, 2004, pp. 542- 563.

Appendix

Reference to Salvini's message regarding the Nigerian immigrant accused of killing a young Italian girl:

Reference to Salvini's post projecting himself as a lover of Italy to his core and the only possible candidate to "liberate" the country.

Reference to Salvini's use of evoking Italian food to emphasize his Italian identity.